Wolves from the past: living with sabertooths

If I could travel back in time to the late Pleistocene of Rancho la Brea in California, I would sure try to set the controls of my time machine so as to coincide with one of the rare entrapment episodes, when the trashing of one large bison or horse trapped in the sticky asphalt attracted dozens of large, hungry predators. It has been calculated that one such episode every ten years would be enough to account for the thousands upon thousands of fossils accumulated at the site, so for most of the time life around the tarpits would be business as usual, and our trip around the area would be just like any safari in today’s African reserves -meaning that the big carnivores would be rather difficult to come across! We would probably drive for hours and see impressive herds of mammoths, horses and bison, but we would just wonder, where the carnivores are?

But if our arrival coincided with an entrapment episode, there is one carnivore we would be more likely to see than any other: the dire wolf, Canis dirus. Known from the bones of more than 1600 individuals from the site, this was obviously one of the dominant predators in the area, and it would stand its ground to such impressive competitors as the sabertooth cat Smilodon fatalis or the even larger American lion, Panthera atrox.

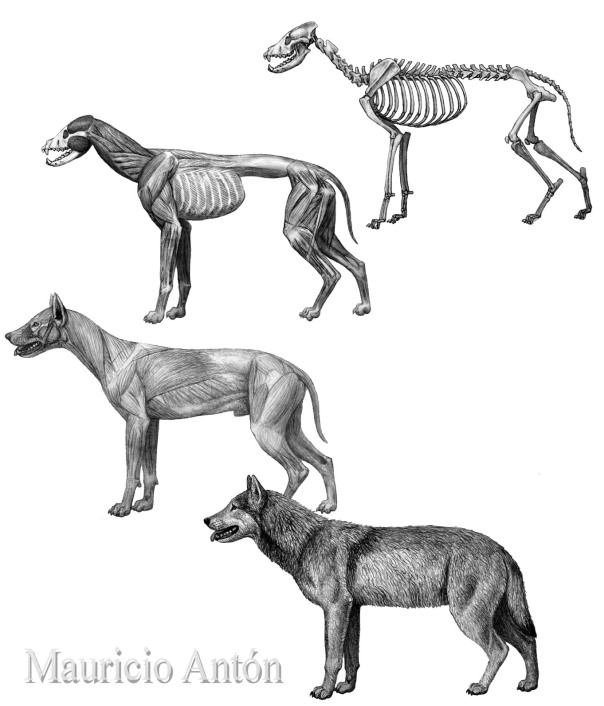

What did Canis dirus look like? Reading the paleontological literature I came across texts describing it as a “hyena-like wolf”, with short legs and a massive head with a powerful crushing dentition. However, a visual inspection of dire wolf fossils showed them to be perfectly wolf-like to me. In order to get a clearer idea of how the animal would look in life, I made a careful drawing of the skeleton using as main reference the descriptions, photographs and measurements made by American paleontologist John Merriam, together with my own photos of dire wolf fossils from different sites.

The result: a skeleton that showed only slight differences from that of a modern gray wolf, which can be summarized as follows: the dire wolf was on average a little larger, with a slightly larger head and feet that were a bit shorter. Those differences were clearly evident when you compared the measurements, but they were so slight that the overall visual impression when looking at the skeleton was overwhelmingly wolf-like.

Then I proceeded to add soft tissue from the inside out, starting with the deep muscles -those whose attachments leave clearest impressions on the bone- and then adding more superficial layers.

Here is my step-by-step reconstruction of the anatomy of the dire wolf, Canis dirus

To reconstruct the animal’s fur, I used as reference the coat of its closest living relatives, that is, wild extant members of the genus Canis. In these animals, from jackals to coyotes to gray wolves, fur color patterns are variable but can be described as variations on a theme, and a very stable one, so the phylogenetic affinities of Canis dirus leave us little room for invention in terms of its coat colour.

So I think that in our time travel we would come across packs of very wolf-like animals, strong and resourceful canids that were able to thrive in an environment packed with the most dangerous competitors. Their extinction, like that of their fearsome felid enemies, is a fascinating, standing mystery.

Here I show the dire wolf in its environment in late Pleistocene North America, with a herd of Columbian mammoths on the background

All art published in our book “Dogs: their fossil relatives and evolutionary history”, by Xiaoming Wang, Richard Tedford and Mauricio Anton, Columbia University Press, New York 2008.

Posted on 22/09/2014, in Uncategorized. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

Reblogged this on Ethology & Horses and commented:

A cool piece on the extinct dire wolf (Canis dirus), and how similar it really was to present day wolves.

Beautiful. Sometimes things like this make me feel the loss of all these long-gone species. Always your sabertooths, of course, almost more than I can express, but these impressive canids too. I don’t often think about dire wolves. How unfortunate that we cannot observe their behavior and study them in life. Nevertheless, the world keeps changing and nature carries on. There is truly not enough room on the planet if every single long-extinct species were to live! It is wonderful, though, that by such meticulous study and effort you can bring them back to life just a little bit. It is lovely that thanks to your efforts a truer picture of dire wolves (and many other extinct fauna) now exists in the minds of many people.

Thank you Joelle! Yes I think we are fortunate to have the fossil record, so that we can get a bit closer to seeing those extinct animals as they were. But I also think that by studying them we get a deeper view of the living species. It is a little as if you have been looking to a photograph for a long time, and suddenly you discover that photo was just a frame in a long film. Only by looking at all the previous frames do you understand the whole motion, of which your familiar frame was just the last fraction of a second… Life on Earth is a bit like that!

Oh, that is fantastic. I love that perspective a lot!

I believe that the dire wolf was significantly more robust than the gray was it not? It’s ML humerus robustness is almost equal to a cougar I believe?

Also sorry for the double post, but I believe that easterb dires were far less robust than la brea dire wolves.